Considering career training instead of college

by Kate McGee, KUT

Inside a small building off Highway 290 in Manor, dozens of high school juniors are sitting in classrooms. But they aren’t learning English or math. In one classroom, students are building circuits. They’re getting their mechatronics certification, which can be used for various engineering and mechanic jobs. In another room students practice using PCs without a mouse as they work toward their PC technician certification.

Down the hall, another group of students sits in rows wearing scrubs. They’re reviewing lessons with their teacher to become certified nurse aides.

These students are part of a new partnership between Manor ISD and Austin Community College. Right now, more than 200 students are spending one or two years working to get one of six certifications that can be used to get higher paying jobs directly out of high school.

“When you leave high school, you don’t have to go to Sonic and flip burgers,” says Catherina Okoro, a junior getting her medical assistant certification. “You can go straight to the hospital and see if they can apply you there. You can start working, getting experience, see if what’s you want to do.”

Even though these certifications don’t require a bachelor’s degree, Okoro wants to go to college. Other students, like Mark Zuniga, agree.

“I feel like going to college is something I want to do and need to do to get a better job,” says Zuniga, who is in the mechatronics class.

“I believe everybody can go to college, and everybody can graduate from college — but it’s not for everybody.” Superintendent Kevin Brackmeyer

While many students say they want to go to college, Manor ISD Superintendent Kevin Brackmeyer provides a dose of reality.

“I wanted to play for the Dallas Cowboys, right? Didn’t make it,” says Brackmeyer. “There had to be some reality check there; at some point you realize I’m not going to make it there.”

Last year, only 51 percent of high school graduates in Manor ISD directly enrolled in college after high school.

“I believe everybody can go to college and everybody can graduate from college, but it’s not for everybody,” Brackmeyer continues. “I think we’ve done a lot of students a disservice by telling them that if you don’t go to college you’re a failure.”

Enlarge

Jorge Sanhueza-Lyon

Brackmeyer says it keeps him up at night to think about the students who graduate high school, but don’t really have a plan afterward. He believes the certification program is one solution.

“We just saw this as, ‘Gosh we’ve got to give them something they can fall back on,’ and not have to resort to working, at best, at minimum wage or falling into some very serious cracks that would cause them to not make it out of here.”

This issue is only becoming larger as Manor ISD’s student population grows. Brackmeyer has to figure out how to give more and more students something to fall back on. Last year, 78 percent of Manor students were considered low income by the state. Statistically, those students are less likely to enroll and complete college.

“For a lot of students who come from well-to-do homes, two parents, parents who are engaged, a good support system, they have a lot going for them, and so there’s a lot of help there,” Brackmeyer says. “In a district such as Manor ISD where there is a lot of poverty, that isn’t always the case.”

But if you look at the Austin region as a whole, getting more kids to enroll in college still seems to be the goal—at least in the business community. This fall, the Austin Chamber of Commerce and nine school districts, including Manor, pledged to increase the regional college enrollment rate to 70 percent by the end of this school year. Brackmeyer signed the agreement. But he says that raises another question:

“Let’s say 70 percent go to college. What happens to the other 30 percent?” Brackmeyer asked. “We’re just kidding ourselves if we just say, ‘Oh, the expectation is you go to college.’”

Plus, enrolling in college doesn’t guarantee students will finish.

Now that the certification program underway, Brackmeyer’s next challenge is helping the students who don’t plan to go to college, but aren’t pursuing a certification. Brackmeyer hopes this first class will show the benefits of getting a certification.

“You got a group of kids who are starting out and we expect to be, hopefully, the trendsetters for the high schools and say, ‘Hey, this is another avenue you can take, and it’s working out well.’”

Job-Seeking Grads Look Beyond Manor

by Caleb Pritchard, Austin Monitor

On the morning of May 9, 2013, a black, heavily armored limousine crested a small hill just to the east of Austin and negotiated a mild curve in the shoulderless gauntlet of the incomplete Manor Expressway.

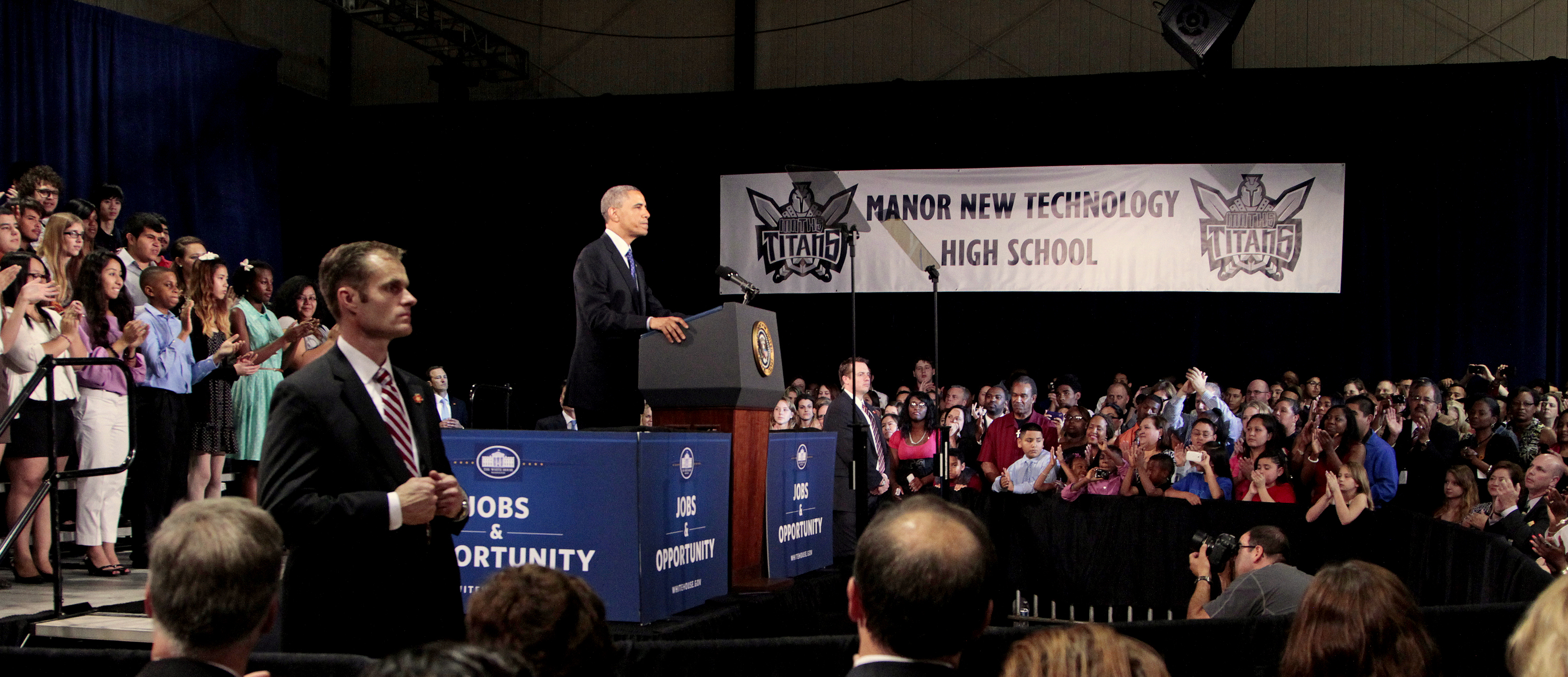

The imposing motorcade drove past temporary Jersey barriers, piles of dirt and heavy machinery before exiting and coming to a rest in a parking lot just off the highway. Its remarkable passenger, the leader of the free world himself, President Barack Obama, stepped out into the muggy air of what had been until recently the rather unremarkable community of Manor, Texas.

Less than a year after his reelection, the president was still wrestling with a national economy that stubbornly refused to break from its holding pattern between recession and growth. Determined to spur the country back into prosperity, the president decided to publicly launch new initiatives aimed at creating jobs across the country. For his backdrop he chose Central Texas, a region whose economy didn’t lose any of its rubber during the Great Recession.

Against this backdrop, the president walked himself into a packed gymnasium and address the gathered students, faculty and staff of Manor New Technology High School.

“And the reason is because our economy can’t succeed unless our young people have the skills that they need to succeed,” the president declared to his rapt audience. “And that’s what’s happening here, right at Manor New Tech. There’s a reason why teachers and principals from all over the country are coming down to see what you’re up to: Because every day, this school is proving that every child has the potential to learn the real-world skills they need to succeed in college and beyond.”

In 2013, Manor New Tech was only five years old, but its remarkable STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) program had earned it enough credibility to warrant this distinguished visit. Two years later, the visit still resonates with those who were there.

“There are days where I’m just like, ‘Did that actually happen?’” says Bobby Garcia, the school’s interim principal. “Just to reinforce the memory, I took one of the pictures they gave us, and I made that my Facebook photo. Now, every time I look at Facebook, I can remember that, yes, that did happen.”

Garcia’s wide-eyed awe about the meeting is matched by his enthusiasm for Manor New Tech’s mission to prepare its students for success – in the president’s words – “in college and beyond.”

Enlarge

Filipa Rodrigues

But for Manor New Tech’s uniquely educated graduates, there’s not much difference between “college” and “beyond.” While droves of people have moved to the town in just the past decade, job opportunities for anyone with a two-year degree or higher have remained scarce. Indeed, it was only last year that job creation of any type showed any hustle.

“It was pretty quiet around here until the Walmart opened,” Vicki McFarland of the Manor Chamber of Commerce said. “Then, the floodgates opened.”

But the laundry list of businesses that are pouring in isn’t quite the type to attract a highly skilled and educated workforce. Near the Walmart, according to McFarland, a shopping center will soon house a nail salon, an AT&T wireless store, and an El Pollo Rico chicken restaurant. A Panda Express and a Wendy’s are slated to open soon after.

Enlarge

Jorge Sanhueza-Lyon

By all appearances, a thriving service sector is emerging to meet the needs of newly planted Manorites. But most of the jobs therein will do little to help the city’s per capita income ($20,219) catch up with Austin’s ($31,990).

And while the Walmart has jump-started a small construction boom along the highway, there still remains a dearth of commercial office space in the city. The Manor Business Park just off the highway comprises two small buildings with aluminum shells. Occupants include a dentist’s office and the Chamber of Commerce. Recently, a large banner hanging next to the Chamber’s door read, “Alcoholicos Anonimos.”

Manor New Tech turned out its first graduating class in 2011 2010. For the alumni who wrapped up a four-year degree on time in May, the hometown doesn’t present much more opportunity than a low-cost bedroom community, a place to rest one’s head between commutes to and from high-paying jobs in Austin or Round Rock.

And beyond its relatively low cost of living, there’s little to keep a young and educated workforce in Manor. Nodules of family-friendly tract housing on the edge of town flair out from the old, weedy grid of 20th century Manor. Aside from a few lo-fi food trucks, the amenities of urban living – the increasingly popular choice among young college graduates – are few and far between.

Garcia of Manor New Tech said that it’s too early to tell whether the school’s alumni are choosing to stay in town or seeking out new digs closer to the cluster of jobs for which they are being groomed. He concedes that Manor is worlds removed from the go-go glitz of Austin’s red-hot tech sector. But, he says, Manor New Tech is not some factory that ships out the town’s best and brightest.

“We don’t want to come off as a brain-drain. Ultimately, there are going to be some kids who are successful wherever they go. We’re really targeting the kids who are bored in class and who weren’t being successful because they didn’t understand the purpose of the work they were doing,” says Garcia.

By nearly every metric, Manor Tech appears to be a resounding success. Garcia says close to 100 percent of its students get accepted into some form of college. Two out of three of those kids are the first in their family to step into higher education.

Of the small pool of alumni who have finished their college degrees, Garcia singles out two who have returned to Manor. They didn’t pursue a job in science or engineering, he says. Instead, they now teach elementary students in Manor ISD.

“I kind of ask myself, ‘Are they starting this fancy semiconductor company or this big innovative lab?’” Garcia explains. “No, they’re not. But in their own way, they’re coming back, and they’re putting their roots down here. They’re still connected to the community, and they’re bringing their experience that they got here and they’re making the community a better place.”

Garcia’s sentiment, whether consciously or not, echoed words once spoken a few hundred feet away.

“That’s what every school should be. That’s what our country should be: caring for each other, helping each other, being invested in each other’s success.”

Those were President Obama’s closing words on May 9, 2013, just before he climbed back into his armored limo and rode west, back down the Manor Expressway.

*Correction: This story has been updated to reflect that Manor New Tech’s first graduating class was in 2010, not 2011.